Sleep for Athletic Performance: The Importance of Pre-Sleep Routines & Consequences of Sleep Deprivation

Introduction

At one point or another, you’ve likely had your parents, coaches, and teachers implore you to get better sleep: “you need your sleep to grow” or “you’ll need a good night's rest before your big game/test to perform well.” They’re right, sleep is very important for your health and development even though it may not always feel like that.

It’s understandable that sleep might not feel as important when there are more exciting things going on. You have social needs (e.g., staying up to message your friends), new experiences to explore, and you’ve developed habits that are hard to break. However, habits like these can hinder your ability to get a good night’s rest.

To be an elite-level athlete, you must make sacrifices to ensure your body and mind are ready to handle the demands of training and competition. Think about how much time you invest into training, proper nutrition, and developing your body. When your sleep is hindered, you are negatively impacting the things to which you devote so much time.

Just think to yourself, “Do Olympic and world-record-holding athletes prioritize fun over their sleep and training?” The answer is almost definitely, no.

Maybe you’ve tried to get better sleep but you were discouraged because you’ve struggled to fall asleep in the past. Getting quality sleep can be tricky because there are many factors that influence our ability to fall asleep, the quality of that sleep, and how we feel when we wake up in the morning.

In this post, I’ll discuss the relationship between sleep and athletic performance, which things you should avoid to get better sleep and the habits you should adopt to improve your chances of having a good night's rest.

What Constitutes “Good” Sleep for Recovery?

Good sleep consists of a combination of two main factors: (1) duration and (2) quality. Both of these factors are important for recovery and sport performance; without one or the other, athletes have a greater chance of making a poor decision or taking too long to react in training and competition.

So, where do you start? How much sleep is enough and what influences your quality of sleep. Here are some general recommendations from the literature:

Sleep Duration

Let’s first distinguish that “time in bed” ≠ sleep duration. Sleep latency (time taken to fall asleep) for the average person is between 10-20 minutes. (Ackermann et al., 2019; Walsh et al., 2021) So, if you go to sleep at 10:30 p.m. and wake up at 6 a.m., it’s likely that you’re only getting close to 7 hours of sleep.

However, sleep latency can be delayed further by sport-related factors (e.g., pre-competition anxiety and training at night) and non-sport-related issues, like poor pre-sleep routines and habits (Thornton, 2016; Ackermann et al., 2019) – i.e., sleep hygiene.

The recommended sleep duration for athletes ranges from 8 to 10 hours. (Weiss, 2006; Samuels & Alexander, 2013; Barnes, Sheppard, & Stellingwerff, 2016; Thornton, 2016; Vitale et al., 2016, Vitale et al., 2019) After a game, a heavy training day, or a poor night's rest, athletes should opt for 9-10 hours of sleep or extend their typical night's sleep by two hours. (Thornton, 2016; Vitale et al., 2018; Walsh et al., 2021)

Alternatively, an adequate amount of sleep can also come from mid-day naps. Based on the 2016 recommendations to American olympic and Canadian elite athletes, mid-day naps can help if athletes aren’t achieving their prescribed 8-10 hours of sleep. Specifically, naps that consist of 1 hour of sleep - before 2pm, (Vitale et al., 2016) 30 minutes between 2-4pm, (Barnes, Sheppard, & Stellingwerff, 2016) or ~90 minutes a few days each week if not achieving 8-10 hours of sleep. (Barnes, Sheppard, & Stellingwerff, 2016)

Sleep scientists even suggest that daytime naps of 60-90 minutes can improve learning and skill potential in athletes - in other words, “the human brain continues to learn in the absence of further practice, and that this delayed improvement develops during sleep.” (Walker and Stickgold, 2005, p.1)

Key Points

Time in bed ≠ sleep duration – the average person takes 10-20 min to fall asleep but this can be prolonged by sport and non-sport related factors.

The recommended sleep duration for athletes ranges from 8 to 10 hours – opt for 9-10 hours after an intense training session.

Sleep extension of 2 hours or 30-60 minute naps before 2 PM can help if athletes cannot achieve their 8-10 hours.

Sleep Quality

Sleep quality is very important, it has an influence on recovery, cognitive functioning and how alert we feel when we wake up. We are likely to get better quality sleep when our brains are able to access two main stages of sleep for longer periods of time.

Without diving too deeply into the stages of sleep, there are four stages and two of them are paramount for feeling recovered: (a) deep sleep and (b) rapid eye movement (REM). Some of the benefits of each stage include:

REM - individuals who get enough REM sleep tend to be better at interpreting others emotions and tend to process external stimuli better.

Deep Wave Sleep - improved tissue repair and growth, and cell regeneration. Strengthens the immune system.

We spend roughly 45-50% of our time asleep in these stages but, if we’re not careful, our habits and routines can impact our ability to access those stages.

What in the world is “Sleep Hygiene”?

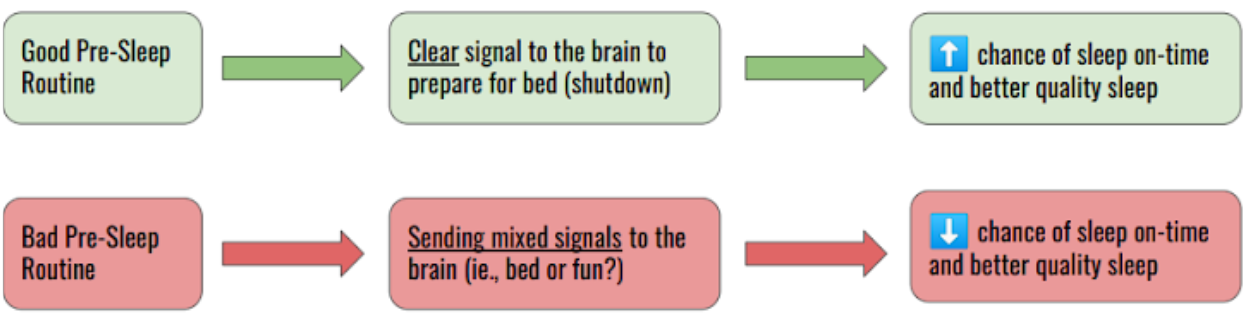

Sleep hygiene refers to the habits and routines that you have prior to bed that impacts your quality and duration of sleep. At its simplest, sleep hygiene consists of the things you do before sleep which send your brain implicit and explicit signals to let it know whether it should wind down or stay alert.

Sleep hygiene influences sleep latency, how many times you wake up during the night, and your ability to reach the deeper and more restful stages of sleep. Good sleep hygiene consists of not only making good decisions prior to sleep but doing them consistently. In order for your brain to recognize these habits as signals to sleep, it must see them performed consistently over a period of time.

Good sleep hygiene is all about putting yourself in the best position to sleep well each and every night. — Sleep Foundation, 2021

Sleep Hygiene: Good Practices & Habits to Avoid

So, what are the things you can do to improve your sleep? Recall from earlier in this article that sleep hygiene is all about doing things that send your brain the right signals, not mixed messages. Your actions should be a clear, unambiguous reflection of your intentions.

Your brain is like a young child or puppy, it will stay up all night playing if you keep giving it stuff to do — even if it’s physically exhausted. You need to give it some time to decompress, it’s unrealistic to expect it to flip a switch from “on” to “off” — it’s brain chemistry, not magic.

Below is a non-exhaustive list of good sleep hygiene strategies and things to avoid. If you would like to explore more tips or are interested in reading about the nuances of sleep, click here or check out the Canadian Sport Institute’s guide on page 20.

How Sleep Impacts Performance

There are a few domains of performance to highlight here. As an athlete, you need to make good decisions, anticipate and react quickly to perform well in competition. In addition, athletes need to make decisions that allow them to recover so that they may train and compete at their peak potential.

Good Sleep Giveth, Bad Sleep Taketh Away

In other sports, extended sleep has shown to improve reaction times (0.15 sec - almost half the time it takes a 95mph fastball to reach the plate), improve sprint times in the 40-yard dash, and improve performance in a variety of sports (tennis, basketball, swimming, etc.). (Thornton, 2016; Walsh et al., 2020)

A lack of sleep also has the potential to seriously impair performance. In the figure below, NBA players who slept more than eight hours tended to perform better whereas those who slept less than eight hours made more mistakes. (Walker, 2017)

Reproduced from Matthew Walker’s book, “Why We Sleep” (2017).

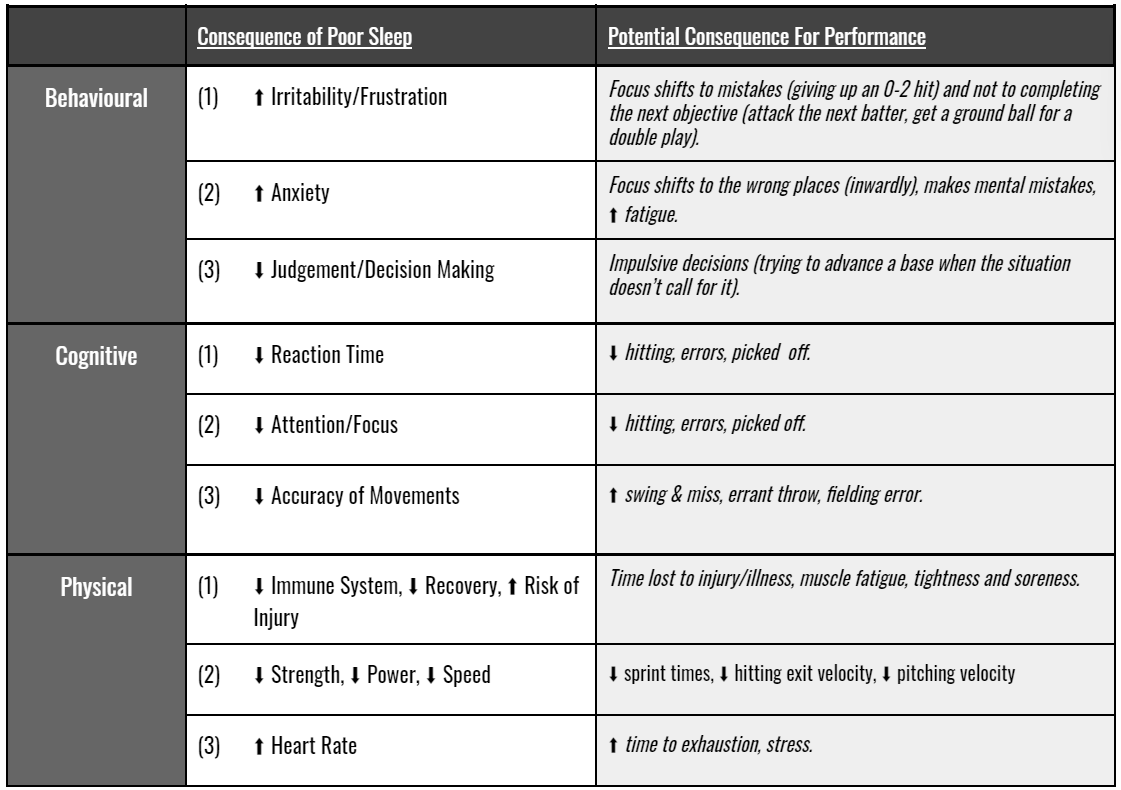

A lack of sleep or poor sleep quality can impact your (1) behaviour and emotions, (2) cognitive performance, and (3) ability to recover. All of these things can be influenced by a single bout of sleep deprivation or a few days of poor sleep.(Walker, 2017; Walsh et al., 2018; Walsh et al., 2021) In the table below, you will find a few examples of how poor sleep could affect each domain of performance for you as a baseball player.

Trying to get good sleep before a game is not enough, the consequences of poor sleep extend beyond competition as well. For example, poor decisions and increased time to exhaustion could lead to lower quality of practice or inefficient use of time with school work or practice. For physical development, poor sleep can increase evening cortisol (i.e., the stress hormone) levels and interrupt the timing of peak growth hormone levels. (Banks & Dinges, 2007)

Sleep & Injury

Although a lack of sleep can impact an athlete acutely, it also increases the risk of injury and illness. An injury could sideline an athlete anywhere from weeks to months and there’s no greater advantage for an opponent than to catch up and surpass all the training you’ve done while you’ve been sidelined.

Sleep has a critical role in lowering those odds of being sidelined. Reproduced from Walker’s (2017) book, “Why We Sleep”, the graph below illustrates the relationship between average duration of sleep and risk of injury for high school athletes. From the image, it should be evident that there is a substantial difference in risk of injury between those with >8 hours and those with <7 hours sleep.

Further supported by earlier work, Mileweski et al. (2014) found high school athletes were 1.7 times less likely to be injured if they averaged eight or more hours of sleep per night when compared to those who slept less than eight hours per night.

Conclusion

Whether you’re a high level athlete or not, sleep has an incredible power to enhance or impair your daily functioning. Many of the behavioural, cognitive and physical effects of sleep are essential for peak athletic performance. Furthermore, these effects are governed by the amount of sleep and the quality of that sleep.

The extent to which you can capitalize or be affected by sleep is largely influenced by your pre-sleep routines. The messages that you send your brain — during your pre-sleep routine — need to be clear and sent on a consistent basis that it’s time for sleep.

Although there are some things that are out of your control (e.g., training, competition, work and school schedule, etc.), the habits you have before you sleep are well within your control. No one is forcing you to watch TV, message your friends, or play video games late at night — those are choices.

This is not to say you have to be perfect. You can still make good choices consistently and have a cheat day or make an exception here and there (like a cheat meal).You need to reward yourself for being disciplined otherwise it’s not sustainable. However, if you are choosing to stay up late several times per week, before a game, or after a physically intense day, you are setting yourself up for failure.

“We are free to choose our paths, but we can't choose the consequences that come with them.” — Sean Covey, 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens

REFERENCES

Ackermann, S., Cordi, M., La Marca, R., Seifritz, E., & Rasch, B. (2019). Psychosocial Stress Before a Nap Increases Sleep Latency and Decreases Early Slow-Wave Activity. Front. Psychol. 10(20), 1-14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00020

Banks, S. & Dinges, D. F. (2007). Behavioral and Physiological Consequences of Sleep Restriction. J Clin Sleep Med, 3(5), 519-528.

Barnes, K., Sheppard, J., & Stellingwerff, T. (2016). Sleep: Best practices for athletes. Canadian Sport Institute. Website: csipacific.ca

Mileweski, M. D., Skaggs, D. L., Bishop, G. A., Pace, J. L., Ibrahim, D. A., Wren, T. A., & Barzdukas, A. (2014). Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 34(2), 129-133.

Samuels, C.H. & Alexander, B. N. (2013). Sleep, recovery, and human performance: A comprehensive strategy for long-term athlete development. Canadian Sport Institute. https://sportforlife.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Sleep-Recovery-Jan2013-EN.pdf

Thornton, L. (2016). Elite athletes and sleep: How much are they getting? What happens when they don’t get enough? Why short term sleep extension might be a performance enhancement. Olympic Coach, 27(1), 4-11.

Vitale, K. C., Owens, R. L., DeYoung, P., Stuhr, R., & Malhotra, A. (2016). Sleep Hygiene for Optimizing Recovery in Olympic/Paralympic Athletes. Olympic Coach, 27(1): 21-33.

Vitale, K. C., Owens, R., Hopkins, S. R., & Malhotra, A. (2019). Sleep hygiene for optimizing recovery in athletes: Review and recommendations. Int J Sports Med, 40(8), 535-543. doi:10.1055/a-0905-3103.

Walker, M. P. & Stickgold, R. (2005). It’s practice, with sleep, that makes perfect: Implications of sleep-dependent learning and plasticity for skill performance. Clin Sports Med, 24, 301-317

Walker, M. P. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Walsh, N.P., Halson, S.L., Sargent, C., et al. (2021). Sleep and the athlete: Narrative review and 2021 expert consensus recommendations. Br J Sports Med, 55, 356–368.